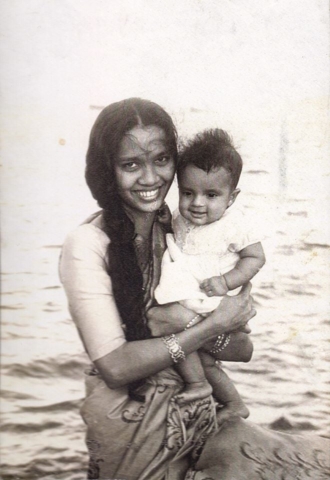

My mother, Jacintha Mohanraj, was 18 when she married, 19 when she had me, 22 when we moved from Sri Lanka to America, arriving on a cold Christmas Day in New England.

Jacintha had two more daughters after me; while my father worked long hours as a doctor at New Britain General Hospital, she kept our home spotless, cooked incredible Sri Lankan food with inadequate ingredients for her young family, and was a constant support to others in the community. She also tried to get her GED, but it wasn’t easy to study while managing three small children, with her parents and siblings in other countries, and she never quite managed to pass.

My family has always valued education highly — my father’s father was principal of three schools, including one he built up from scratch on the island of Delft, just off the coast of Sri Lanka; he was so beloved an educator that they raised a statue there in his name. Many of my relatives were teachers — in my family, we tend to be teachers or doctors. So I think it must have particularly pained my mother that due to the circumstances of immigrant women’s lives at the time, she didn’t get a chance to continue with her education.

My parents struggled to send me to the best private high school they could afford — like many immigrants, they invested their best hopes in their children’s education and future success, and made many sacrifices to cover tuition, books and fees.

It wasn’t easy for them — my parents had just bought their first house when I started high school, and there were times in those early years when the tuition was late, or I had to get books from the library because we couldn’t quite afford to buy them. But somehow, they managed to send me and my sisters to great high schools, and later, to pay for our college; being free of college debt was a tremendous gift that has opened up so many opportunities in my life, and I know it wasn’t easy for them to manage.

I went to the University of Chicago, and perhaps a little intoxicated with the freedom of it all, and with having a boyfriend for the first time, I missed quite a few early morning calculus classes, which led to a rude awakening when I flunked my freshman calculus class. I was, I have to admit, slightly terrified when I called my parents in Connecticut, to tell them I’d flunked a class — I actually had my boyfriend (that they didn’t know about) hold my hand when I made the call, because I was so nervous; I was crying when I told them.

They were actually very kind about it on the phone that day — although my parents had high expectations for me and my studies, they also wanted me to be happy. “Try your best, kunju,” was all they asked of me, really. ‘Kunju’ is a Tamil word, like ‘darling’ — my parents spoke multiple languages fluently, coming from once-colonized Sri Lanka. My mother speaks three languages (Tamil, Sinhalese, and English), despite not getting her GED.

When I came home for Christmas that year, my mother picked up my calculus textbook and started paging through it. As she went, she looked increasingly bewildered. “I don’t understand — how are you having trouble with this?”

It turned out although Sri Lanka is a tiny island nation (the size of Connecticut and Massachusetts put together), and despite dealing with the aftereffects of colonization, Sri Lanka’s educational system was still more advanced than ours in many ways; before the ethnic conflict, for example, they had a 99% literacy rate. (America currently stands at 86%.) My mother had covered calculus in her convent high school math classes, and was smart enough that she’d breezed through it.

I think of my mother, when I think about serving on the high school board as a trustee. It’s one of the great sadnesses of my life, that though it was no one’s fault, circumstances conspired to keep her from access to the kind of education that would have let her thrive and shine.

Jacintha was busy enough when her girls were young, but after we’d all graduated and flown off to our careers in other cities (ending up as a professor and two doctors), my father was still working long hours, and she didn’t have the consolation that a life of the mind might have provided. She was clearly smart as a whip, but our educational and social systems failed her.

Now I look forward to the next generation, where my parents’ hopes and my own hopes reside. My children have attended our local public schools; my daughter will be entering OPRF as a freshman this fall. As a board member, my focus will be on trying to make sure *all* of our children are well-served by the high school, so they can achieve to their fullest potential.

I want to be sure that our students have teachers who are brilliant at what they do, and who are eager to guide and support students in their studies. I want teachers and staff to be well-resourced, so they can concentrate on the students’ needs.

Perhaps most importantly, I want students from marginalized and disenfranchised backgrounds, struggling with economic or other challenges, to have everything they need to succeed in high school and beyond. None of them should look back, like my mother, with frustration at opportunities denied.

I want our students to fly high and strong.

I want our school to do everything we can, to help them build their wings.

******