It’s going to take me a long time, I think, to fully integrate all my thoughts from the Pakistan trip. I didn’t expect that. I’ve been to India, after all — to Agra and Delhi, to Chennai and Kodaikanal — and of course to Sri Lanka many times; I think I’d been assuming that Pakistan would feel fairly similar.

Dear readers, it did not.

I hadn’t understood the extent to which Pakistan is a theocracy. The closest I’ve been to somewhere like that was the three years I lived in Salt Lake City during grad school, and specifically, the time I went down to a conference at Brigham Young University in Provo. Mormons aren’t supposed to have hot caffeine; it’s considered a drug — so no coffeeshops on the BYU campus. That was startling to me; colleges typically run on coffee and tea.

I think it generally takes having a serious majority population of a single religion to have that religion imposing its strictures legally on the entire population. You can see the weight of Christian dominance all through the U.S., from Sunday liquor laws to the overwhelmingness of Christmas and more. But still, I’ve always lived in big enough cities that they had very mixed religion populations, so I never really felt the weight of theocracy before.

***

I talked a few days ago here about what theocracy meant for liquor laws in Pakistan (drinking or serving alcohol is illegal for Muslims, who comprise 97% of the population). But the piece that I suppose I knew about theoretically, but hadn’t really understood the force of, has to do with blasphemy.

“The Pakistan Penal Code, the main criminal code of Pakistan, penalizes blasphemy (Urdu: قانون ناموس رسالت) against any recognized religion, providing penalties ranging from a fine to death. According to the US Commission on International Religious Freedom, around 80 people are known to be incarcerated in Pakistan on blasphemy charges—half of those face life in prison or the death penalty. From 1967 to 2014, over 1,300 people were accused of blasphemy, with Muslims constituting most of those accused. According to human rights groups, blasphemy laws in Pakistan have been exploited not only for persecuting minorities but also for settling personal rivalries, often against other Muslims. Though no judicial execution has been carried out under these laws, many of those accused, their lawyers and any persons speaking against blasphemy laws and proceedings have become victims of lynchings or street vigilantism in Pakistan. More than 75 people were murdered for blasphemy between 1987 and 2017.”

— https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blasphemy_in_Pakistan

For most Westerners, the most visible example of this in the literary realm is Salman Rushdie, whose writing and publishing of The Satanic Verses led to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (at the time, the Supreme Leader of Iran) issuing a fatwa in 1989, condemning Salman Rushdie to death for alleged blasphemy.

“The Iranian government has changed its support for the fatwa several times, including in 1998 when Mohammad Khatami said the regime no longer supported it. However, a fatwa cannot be revoked in Shia Islamic tradition.” — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satanic_Verses_controversy

I’m assuming most people reading this are familiar with the Rushdie case — if not, the Wikipedia page linked above is a good summary. Rushdie went into hiding for a long time, and though he eventually came out of hiding and started making public appearance, he was recently (2022) attacked at a literary event in upstate New York, and stabbed multiple times. He survived, but with serious injuries.

***

All of this is preface to say that when I was teaching writing in Pakistan, suddenly I understood that if my students wrote something that was blasphemous — or worse, something that someone THOUGHT was blasphemous — their lives were at serious risk.

As a writer, I’ve never been in that situation. I did write one story about Sita and Rama and Lakshman (“A Princess in the Forest”), where I was a little concerned that some aspects might come across as inappropriate to someone devout, and I ran it by some Hindu friends to see if they thought it was all right. But I wasn’t worried for my safety as a writer; I just wanted to be sure I wasn’t being accidentally disrespectful. I can link to it here, without concern:

http://maryannemohanraj.com/…/the-princess-in-the-forest/

But my Pakistani students have to be so careful. And it’s such a frustrating kind of careful — it’s not like there’s a clear list of topics to avoid, things you can’t say.

***

You’re probably fine writing all kinds of things, and most readers, including religious readers, won’t consider it blasphemy. But you’re always living with the awareness that SOMEONE can decide that you’ve crossed the line, and call out the hounds to hunt you down. They may not even be sincere in their accusation, as seen in this example, where the courts concluded it was motivated by personal gain:

“The police arrested Ayub Masih, a Pakistani Christian bricklayer for blasphemy on 14 October 1996 and jailed him for violation of § 295-C. Muhammad Akram, a Muslim neighbour to Masih, complained to the police that Masih had said Christianity was right, and Masih had suggested that Akram read Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. The same day that Masih was arrested, Muslim villagers forced the entire Christian population of Masih’s village (fourteen families) to leave the village. Masih’s family had applied under a government program that gave housing plots to landless people. Local landlords resented Masih’s application because the landlords had been able to oblige landless Christians to work in the fields in exchange for a place to live. Masih’s application gave him a way out of his subservience to the landlords. Upon Masih’s arrest, the authorities gave Masih’s plot to Akram. Akram shot and injured Masih in the halls of the Session Court at Sahiwal on 6 November 1997. Four assailants attacked Masih in jail. The authorities took no action against Akram or against the other assailants. On 20 April 1998, Judge Abdul Khan sentenced Masih to death and levied a fine of 100,000 rupees. Two judges of the Lahore High Court heard Masih’s appeal on 24 July 2001. Shortly thereafter, the judges affirmed the judgment of the trial court. On 16 August 2002, the Supreme Court of Pakistan set aside the judgment of the lower courts. The Supreme Court noted Akram’s acquisition of Masih’s property and concluded the case had been fabricated for personal gain. The court also noted other breaches in the law of due process.”(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blasphemy_in_Pakistan)

***

The upshot of all this, for me personally, is that I realized I felt completely incompetent to advise my Pakistani students in this regard. I taught a workshop there, on Writing the Taboo, and we talked about writing about sex, writing about money, writing about illness and mental health — but while I wrote RELIGION on the board in big letters, I told them I couldn’t really address it. It was out of my lane.

In part that’s because I’m not religious myself — I was raised Catholic, but left the Church when I was twelve, and have been a cheerful agnostic ever since. (Agnostic, not atheist — the universe is vast, and there may well be Powers I’m not aware of. But I’ve never been able to manage belief in the absence of evidence, so here I am, agnostic. Full of questions, expecting no answers.)

Mostly, though, I felt incompetent to advise them because I don’t live under such strictures. I don’t live in a theocracy, and I don’t think about / worry about blasphemy when I write. So how could I possibly advise them?

I hope they can find Pakistani writing teachers with decades of experience, who can help them through this going forward.

*****

I’ve been trying to think whether there’s any other situation where writing might put my life at risk. I’ve written about socially prohibited subjects, but when you write about sex, the worst you’re likely to encounter is some judgement at the dinner table, fights with your parents, perhaps a bit of social shunning.

But I realized that there was one clearly dangerous writing path — if I’d gone back to Sri Lanka, and worked as a journalist during the decades of the conflict. If I’d told the truth about what the government was doing, and what the Tigers were doing.

Journalists are killed for such things. Journalists are disappeared. Sugi Ganeshananthan‘s brilliant _Brotherless Night_ takes on this topic. http://amazon.com/Brotherless-Night-Novel…/dp/B09X52TJ5P/

I didn’t end up as that kind of writer, but if my life had gone just a little differently, and if I’d been braver, I could have.

Sobering thought.

*****

The other piece of this, though, that I want to highlight, goes back to the uncertainty. If you don’t know what you might say that might strike someone else as blasphemous, and if the stakes are so very high — your life, your family’s lives — then there’s a tremendous chilling effect.

It will always be safer to say nothing at all.

This doesn’t just apply to writing, of course. Consider the woman going out at night on her own, or traveling the world alone, and how she might decide to dress conservatively, modestly, because she never knows who will decide she’s crossed the line, and punish her for it. Consider how many women don’t leave their homes at night, or at all, as a result.

***

I think it was Samuel Delany who said that society will always push you towards the most conservative position it can. (Apologies, Chip, for the paraphrase, and if I got the attribution wrong. My memory isn’t always reliable.)

For a writer, that means that it’s tremendously easy to start policing yourself. To only write about safe topics. Even if the odds are very small that someone will notice and come after you, if the stakes are high enough, it’s a real question — why take that risk?

You take the risk if it matters to you. If you are so upset and angry about the damage that is being done that you feel you have to write about it, knowing what it might cost you.

***

That’s the closest I could get to advice for my writing students, and it felt…risky…to even say that. I wish I had a better answer for them. I felt helpless, watching them work through these issues in workshop, discussing the use of pseudonyms (which can always be potentially unmasked), the challenge of writing things you can’t talk about having written in public…

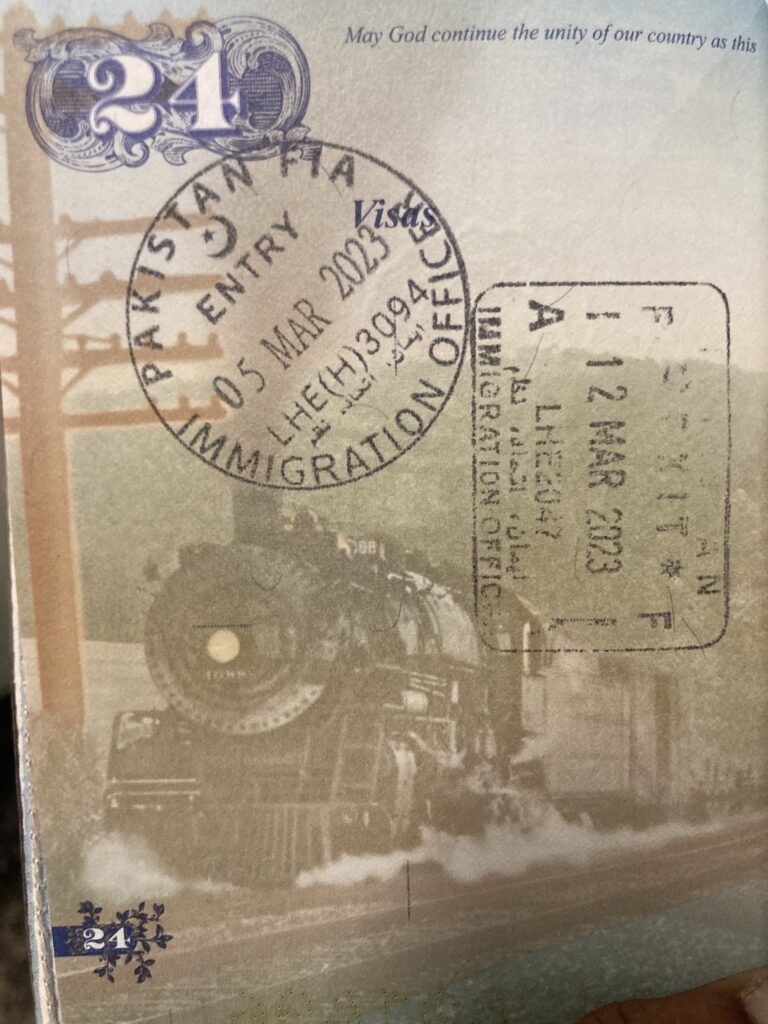

This was nothing I anticipated, when Usman Mlk asked me if I’d be willing to go teach science fiction writing in Pakistan for a week. That week changed my perception of the world, dragged me out of my safe secular life.

I’m going to be thinking about this for a long time, and holding my students in my heart.

Let them be brave.

Let them be safe.

******