I think I’ve mentioned that my father-in-law was a federal district judge; I’m not sure I’ve made it clear that he was a pretty big deal. I’m appending a long tribute article below, from Law360, that goes into some detail.

Some of my best memories of Ron were of him explaining some of his cases to us over the dinner table. They weren’t always easy to follow — many of them involved pretty dense aspects of patent law. But it was still always great, listening to him patiently explain.

You may not think this kind of IP / patent law has a lot to do with you, but it probably does. For example, we were all affected by Ron’s ruling in 1995 that led to certain safe harbor provisions enacted for internet service providers.

If I’m remembering and understanding right, in Religious Technology Center v. Netcom On-Line Communication Services Inc., the question was whether ISPs could be held responsible for what users did with their service. His ruling essentially said that that was technologically impossible; it would be like asking phone companies to be responsible for monitoring everything anyone said on the phone.

Kevin and I were talking about it last night, about how Facebook and Twitter and such are now trying to moderate their giant platforms, and that maybe we’re getting to a point with weak AI where that might actually be possible? It’s a mess right now, but maybe it will get better as they keep working on it. But in 1995, there was just no way to do it. If he’d ruled differently, I don’t know what would have happened, but I suspect it might have had a serious negative effect on the early internet.

I am not a lawyer, and I may be misrepresenting much of this — it’s a memory of a conversation from almost twenty years ago. Mostly, I remember sitting at the dining table with Ron, listening to him talk. All of the lovely things they say about him in this article match my recollection of his personality and character.

The law was lucky to have him, and so were we.

(They say in the article that Ron originally wanted to be a mathematician — I’m not sure I knew that! I bet it made him happy that his son became one.)

*****

Judge Ron Whyte Dies At 80, Leaving Storied IP Legacy

By Dorothy Atkins

Law360

(April 12, 2023, 9:02 PM EDT)

–Retired Senior U.S. District Judge Ronald Whyte, who presided over thousands of Silicon Valley disputes over more than 27 years, died at age 80 this week, leaving a storied judicial legacy for his work crafting nationally recognized patent laws and guiding colleagues on and off the bench.

Judge Whyte helped create local standards for courts to review patent cases that other federal districts across the country have since adopted, and he was a major contributor to the federal judiciary’s patent case management guide.

Judge Whyte assumed senior status in March 2009 and retired in November 2016 after serving on the bench for more than two decades since he was nominated by former President George H.W. Bush and confirmed to the federal bench in 1992.

During his time as a federal judge, Judge Whyte decided more than 7,000 civil cases and roughly 400 patent cases. Before his federal appointment, he was a judge on the Santa Clara County Superior Court for three years in a position that would regularly require him to hear 25 motions a day, the judge recalled in 2016, speaking before 200 lawyers, judges and academics who gathered to celebrate his career.

Although his uncle and father were judges, Judge Whyte never intended to pursue the profession as an adolescent, and he hoped to have a career as a mathematician, he recalled in 2016. He decided mathematics was not the profession for him after he earned an undergraduate degree in the subject from Wesleyan University in 1964.

He eventually turned to law, earning a law degree from the University of Southern California School of Law in 1967, and he served three years in theU.S. Navy from 1968 to 1971 as part of the Judge Advocate General Corps, according to the Federal Judicial Center.

Judge Whyte was born in Pomona, California, and in 2016 he said he always considered California his home and turned down jobs in other states — including in Phoenix, Arizona, which he refused because of temperatures that frequently reached 100 degrees or more. Eventually, he accepted a job at San Jose-based Hoge Fenton Jones & Appel and worked in private practice for 18 years before joining the bench.

Throughout his career, Judge Whyte developed a reputation not only for his work forging new guidelines in patent law but also for his generosity, his humble demeanor, his willingness to help others and his ability to gain the respect and admiration of those around him.

Chief U.S. District Judge Richard Seeborg of the Northern District of California said Wednesday that Judge Whyte was a “revered and beloved” member of the district court for over two decades and that he combined his “brilliant mind, prodigious work ethic and total integrity with humility, humor and compassion.”

“Simply put, he was not only a model federal judge but also a lovely human being,” Judge Seeborg said. “He particularly stood out in the area of intellectual property law in which he forged a national reputation. On a personal note, he was a mentor and friend who I will sorely miss.”

Retired U.S. District Judge Jeremy Fogel, now executive director of the Berkeley Judicial Institute, told Law360 on Wednesday that he came to know Judge Whyte in the late 1980s when both were superior state court judges in California.

The pair stayed in touch after Judge Whyte was confirmed to the federal bench in 1992, and Judge Fogel sought his advice in 1998 when former President Bill Clinton nominated him for the federal bench.

As Congress vetted Judge Fogel for the position, Judge Whyte gave him tips on how to navigate the politics of the confirmation process, and he suggested that Judge Fogel start to study patent laws as soon as possible, given that the vacant federal judicial seat was in the heart of Silicon Valley where numerous patent cases were being litigated at the time, Judge Fogel recalled.

After Judge Fogel was confirmed to the federal bench, he was assigned 33 patent cases on his first day, even though he had never presided over such cases in state court, and Judge Whyte’s advice proved invaluable in managing his caseload, Judge Fogel said.

Over the following decade, Judge Fogel said, Judge Whyte became his mentor and go-to person when he needed help thinking through a difficult case, a challenging problem, or if he “just had a bad day.”

“It’s just hard to imagine a better colleague,” Judge Fogel said. “I treasured his friendship and his collegiality so much.”

Judge Whyte was thoughtful and humble, both inside and outside the courtroom, Judge Fogel said, and he treated everyone well while setting a respectful tone in the courtroom.

He had an even-keel temperament and would always be thoughtful about his advice, avoiding “knee-jerk responses,” and he encouraged judges to issue “sober and reflective” orders, and to think about all the potential angles and repercussions in judicial decision-making, according to Judge Fogel.

Judge Whyte’s demeanor, strong values and consistency serve as a guide in how judges can foster collegiality among the judicial bench and help each other be resilient and avoid burnout, he said.

“It was a privilege to serve with him,” Judge Fogel added.

U.C. Berkeley law professor Peter S. Menell, who is the director of the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology, told Law360 on Wednesday that he first met Judge Whyte in the mid-1990s when Menell created the center, and hosted an event in 1998 on patent law that drew roughly 40 judges from across the judges who were seeking guidance on how best to manage patent cases.

Menell recalled that Judge Whyte was presiding over a wave of patent cases in Silicon Valley at the time, and so he gave a presentation on his local patent rules, which were quickly adopted by many of the other judges at the conference.

“Judge Whyte was so humble gracious and warm, he’s not one of these judges [who] is instilling fear,” Menell said. “He was a great communicator and I could see why the practitioners and other judges really warmed to his demeanor.”

Menell noted that Judge Whyte also issued a precedent-setting ruling in 1995 in Religious Technology Center v. Netcom On-Line Communication Services Inc., which was codified into law when Congress enacted the Digital Millennium Copyright Act three years later creating certain IP safeharbor provisions for internet service providers.

“He was such a thoughtful judge that he could recognize when technology was shifting the tectonic plates of the major industries that emerged in Silicon Valley, and obviously patents and copyrights played a very significant role,” Menell said.

Menell added that Judge Whyte was a particularly good listener, who spoke softly and deliberately, and he never talked down to anybody.

“There was never a comma out of place. He had a measured quality that made him a very easy to interact with,” Menell said. “He was so humble, even though he was a federal judge he would make you feel like he was at your level, and that’s not always easy to do when you have some biggest egos battling these cases.”

Following the news of his death, former colleagues, friends and former mentees took to social media, sharing their memories of the judge and commending him for his contributions to patent laws.

Stanford Law professor Mark Lemley recalled arguing his first federal court case in front of Judge Whyte, whom he described as “generous, kind, thoughtful, intelligent and humble.” He said he worked with the judge to try to make patent jury instructions comprehensible to laypeople.

Lemley also remembered Judge Whyte for his sense of humor, recalling an exchange in which he presented Judge Whyte with the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology’s Distinguished Service Award in 2001.

Upon receiving the award, Judge Whyte jokingly told Lemley that he was surprised to receive the award because Lemley had just filed an amicus brief arguing that he should be reversed in eBay v.Bidder’s Edge.

Lemley added that the one argument he did win with Judge Whyte was forcing him to take cookies home after their cookie parties.”He was truly the dean of the patent community and a lovely person,” Lemley said. “I will miss him.”

Paul Grewal, Coinbase’s chief legal officer, who spent half a decade as a magistrate judge in the Northern District of California, said Judge Whyte was a wonderful judge and friend, and he was”among the most honorable of men ever to serve this country.”

Grewal said California’s Northern District and the entire federal judiciary had “lost a giant.”

“Judge Whyte was a yardstick for so many other judges in so many different ways,” Grewal said.”Just asking ‘What would Ron do?’ was an easy, surefire way to get to the right result in the right way.”

Timothy T. Hsieh, an assistant professor at the Oklahoma City University Schoolof Law, recounted on LinkedIn that Judge Whyte was generous with his time, helping him in his research into patent laws in recent years, even during his retirement, and connecting him with useful sources, including other practitioners who helped him craft the local patent laws.

Hsieh wrote that Judge Whyte’s work and collegiality “not only fundamentally impacted IP and patent law, but jurisprudence as a whole.”

This year, the annual IP seminar, co-sponsored by the Federal Judicial Center, the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology, and the Berkeley Judicial Institute, will be named the Ronald M. Whyte Intellectual Property Seminar in honor of Judge Whyte’s legacy, according to Menell.

“We will miss Judge Whyte greatly, and we hope that this tribute is one he would accept in his characteristically wise, quiet way,” the center said in a statement Wednesday.

–Editing by Peter Rozovsky.

*****

More info on his Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronald_Whyte

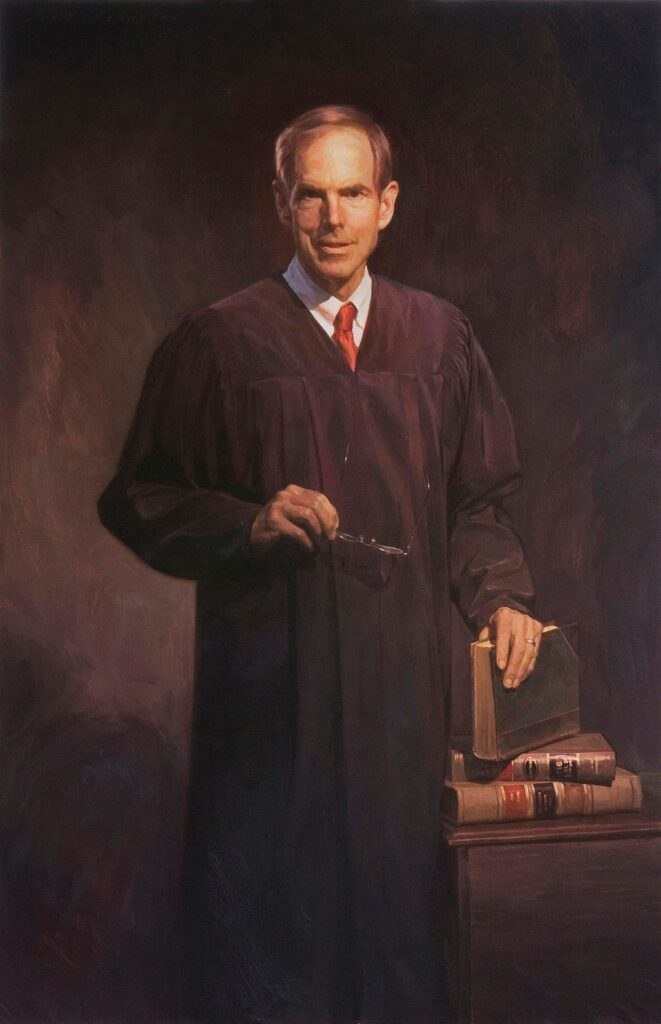

(Judge Ronald Whyte official portrait art by Scott Johnston, oil on linen, 48×30-inches, collection of the United States District Court of Northern California, San Jose)