One of the hardest parts about learning something new is not just that you mess up, but that it so often costs valuable resources when you do. Maybe that’s time, or money, or emotional stability — I can get so frustrated when a thread tangles in the sewing machine.

Usually, I have enough class privilege that I can afford small losses in time or money — a wasted sheet of watercolor paper, for example, when I paint a sloppy line. That makes it much easier for me to take risks, to try new things. People are sometimes startled by how much I do, but there are reasons for that — I can afford to try things over and over, until I learn to do them right.

People in marginalized communities, people living in economic precarity, generally don’t have that luxury available to them; the stakes are higher if they try new things. They fall farther, faster. (This is why women tend to give up on submitting stories to a market much faster than men do — on average, they don’t have as much cushion for absorbing those rejections and trying again.) This is where community support and mutual aid can be key, and can help to supplement the missing privilege. (Our local mask-making group is full of people who don’t sew, but who are providing materials for those who do.)

It’s not just economic privilege. I’m also culturally trained to be a good student — I have a background that assures me that if I keep working at something, I’ll get better, and I’ve been gifted a bone-deep assurance born of years and years of practice (at piano, at reading, etc. and so on) that those teachers telling me I’ll get better are telling the truth. I had strong support from my parents, from my teachers, in my childhood education, and that provides an invaluable backbone of confidence. A child growing up without those supports is going to have a harder time trying again after a failure.

I may never be as good as the professionals, but I assume I can get to competent on most things, with sufficient application of time and effort and money and patience. That assumption is what lets me try so many things, and succeed. That assumption is based on a foundation of privilege.

(Also, I can sometimes afford better-than-basic tools, which mean that I mess up less often than I might. A good sewing machine is worth its weight in gold right now.)

I still make mistakes. Dumb mistakes, heartbreaking mistakes. See these masks? I was trying a different method — instead of elastics behind the ears (which chafe over the course of a long work day), I went for two elastics around neck and head.

But I made a big mistake — I cut them to 8 and 10 inches (per recommendation), knotted the ends and sewed them in, and I did a dozen masks before I thought to actually try one on — way too tight. It just wasn’t going to work. Gah. I still don’t know what I did wrong there — maybe it was actually 10 and 12, and I remembered it wrong? Maybe I knotted my ends, using up elastic, and they’d sewn theirs in, using less. I don’t know.

The 10″ elastic worked for the neck. I ended up cutting off the 8″ entirely, and now I’m making fabric ties to go around the head, and that’s a fine option; some people will prefer those. But the elastics I cut off are now too short to use even for ear pieces; they’re just wasted.

And I have to admit, it made me want to cry when I realized that, because even though I have enough elastic on hand for my own work right now (thanks to people sending me money for mask-sewing supplies when my own budget was running out), elastic overall is precious. It’s a scarce resource worldwide and wasting any of it makes me feel a little sick.

But I’m trying to put that aside, to accept that in learning a new thing, there will be mistakes. There will be wastage. It takes me 15 minutes to sew a mask now, but if you’re sewing a mask for the first time, expect it to take 45 minutes. And that extra 30 minutes isn’t truly wasted — it’s spent, a necessary part of the process of learning. You are human, you will make mistakes, you will spend thread — I have an entire bobbin of miswound thread that I should just throw out, and I haven’t quite been able to bring myself to do it yet, but it has to be done — and it’s okay. Try not to spend too much.

When you make a mistake (note that I said ‘when,’ not ‘if’), take a breath, maybe take a walk, because sometimes mistakes tend to compound. You’re frustrated, and so you’re hasty, and that leads to more mistakes. If you’re learning something really new — maybe you’ve bought a $40 sewing machine, and are trying to teach yourself how to sew from YouTube videos (see mine in comments below) — then allow yourself a lot of time for mistakes. It’ll be okay.

Remember that you’re not somehow terrible at this just because you make mistakes. Ask if you have questions. It’s completely normal to be confused. (And for the dudes out there — I know you’re not culturally taught to see sewing as a thing you can do, but it’s totally a thing you can do. Your fingers aren’t too big for it, I promise you.)

Sometimes Kevin and I talk about our work. I am such a fan of instant gratification, and one of the real challenges I have with writing novels is that it feels like this endless process of fixing my mistakes. I lay some words down, and they’re all right, but then I realize this entire character needs to be cut, and the novel actually should start twenty years earlier, and so I have to persuade myself that it’s worth doing the work, fixing the mistake. And novels are particularly frustrating beasts, because sometimes you do all that, and then two years later, you realize that the book really should start twenty years later instead…

…but Kevin is a theoretical mathematician, and he spends most of his work time pursuing paths that turn out to be dead ends, and when he talks about that, it makes my stomach churn, honestly. I can’t imagine spending years without accomplishing something. But he’d tell you that crossing off unproductive paths is also an accomplishment. Learning that the 8″ elastic is too damn short is useful information.

(All those scientists frantically working on a vaccine? This is how their work goes too. This didn’t work? Okay, good, cross it off, publish so everyone knows. On to the next thing.)

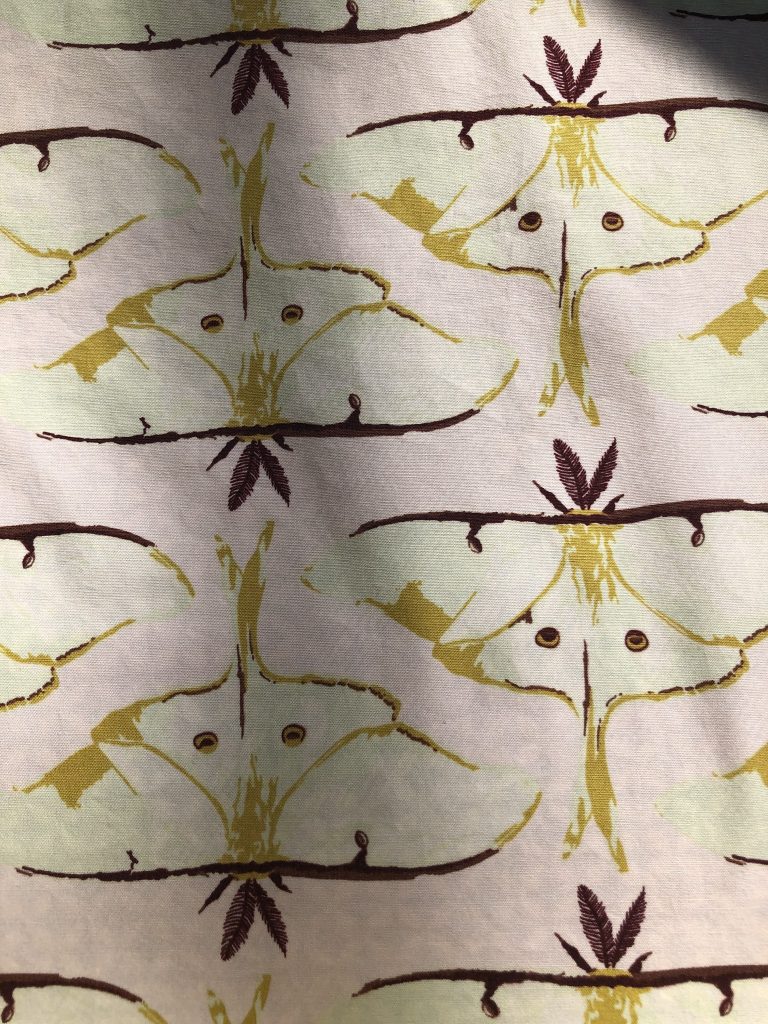

This set of masks is going to ICU staff at my sister’s hospital in New York. I know they’re already moving past peak, so a part of me is fretting that I’m too late and slow on this, but I think that’s silly — we’ll be masking for a long time. I’m hopeful that they’ll have plenty of PPE for work, but that these might serve to cover their other masks to help them last longer, or to just be more cheerful, or perhaps they’ll wear them walking to the grocery store instead.

If these masks can make their lives a little easier, a little brighter, that’s all I ask. It’s worth some anxiety and frustration, I think. It’s worth working through the mistakes.